Dr Richard Axelby hoped to interview Thakur Singh Bharmouri about recent political developments, as he journeyed along the rough road through the mountains to Bharmour, ancient capital of Chamba district in the state of Himachal Pradesh, India. He arrived to find Thakur Singh’s house closed up. Where was he? Nobody knew for certain but there was talk that he’d left to start campaigning to become the Indian Congress Party’s parliamentary candidate in the April 2019 national elections. In this article, Dr Axelby reflects on the ubiquity of Thakur Singh – a long-time member of the state Legislative Assembly who both represents the Gaddi Scheduled Tribe and is representative of what it is possible to achieve as a poor ‘tribal’ boy from a remote village in mountainous India.

Dr Richard Axelby hoped to interview Thakur Singh Bharmouri about recent political developments, as he journeyed along the rough road through the mountains to Bharmour, ancient capital of Chamba district in the state of Himachal Pradesh, India. He arrived to find Thakur Singh’s house closed up. Where was he? Nobody knew for certain but there was talk that he’d left to start campaigning to become the Indian Congress Party’s parliamentary candidate in the April 2019 national elections. In this article, Dr Axelby reflects on the ubiquity of Thakur Singh – a long-time member of the state Legislative Assembly who both represents the Gaddi Scheduled Tribe and is representative of what it is possible to achieve as a poor ‘tribal’ boy from a remote village in mountainous India.

His was the first face I saw when I woke in the morning and the last when I went to sleep at night. Looking down on me from the wall-cupboard next to my bed in my small room in a small village in a remote Himalayan valley was a large round sticker: ‘Give Vote to Congress – Thakur Singh Bharmouri’. As a lonely anthropologist doing fieldwork in the Indian state of Himachal Pradesh, this kindly face was a source of reassurance – a wide smile that extended to twinkling eyes, kindly and comforting, dignified but approachable, trustworthy but with a hint of mischief. Wherever I went it seemed that Thakur Singh Bharmouri – the Himachal Pradesh Legislative Assembly member (MLA) for Bharmour – was there with me.

The face followed me around. Walls and shop windows in the District Headquarters were plastered with flyers publicising Thakur Singh’s recent visit as guest of honour at a political rally. Discussing politics in the house of the Pradhan (the leader of the village governing body) I saw Thakur Singh again in a framed photograph of the two men on the campaign trail. Regular appearances in newspapers were illustrated with photos of him triumphantly clasping hands with HP Chief Minister Virbhadra Singh or smiling out of a crowd behind senior Congress leaders. Heading higher into the Himalayas towards the remote Tribal Sub-District of Bharmour I found buildings painted with the slogan: ‘Bharmour ka vikaas, Thakur ji ke saath’ – with Thakur ji, Bharmour will progress. Another slogan simply stated, ‘Give Vote to Congress – Thakur Singh Bharmouri’.

Thakar Singh Bharmouri was rarely seen without his pahari topi – a flat hat with coloured band – that marked him out as a member of the Gaddi Scheduled Tribe. The Indian Constitution recognises the official category of Scheduled Tribe (ST) as people deserving of special care and assistance. The criteria for establishing a set of people as a Scheduled Tribe are loosely defined but rest on a lack of social, educational and economic development – conditions that, at the time of Independence, applied to the Gaddi ethnic group who scraped a living by combining nomadic pastoralism with subsistence agriculture in Chamba District of Himachal Pradesh. Among the official measures brought in to improve the position of ST communities in India was the reservation of seats in State Legislative Assemblies. As the heartland of the Gaddi ethnic group, the Bharmour area is classified as a ‘reserved’ constituency in which candidates must belong to a ST; it is also a tribal sub-district which provides increased budgets to promote education and affirmative action employment schemes.

Thakar Singh Bharmouri was rarely seen without his pahari topi – a flat hat with coloured band – that marked him out as a member of the Gaddi Scheduled Tribe. The Indian Constitution recognises the official category of Scheduled Tribe (ST) as people deserving of special care and assistance. The criteria for establishing a set of people as a Scheduled Tribe are loosely defined but rest on a lack of social, educational and economic development – conditions that, at the time of Independence, applied to the Gaddi ethnic group who scraped a living by combining nomadic pastoralism with subsistence agriculture in Chamba District of Himachal Pradesh. Among the official measures brought in to improve the position of ST communities in India was the reservation of seats in State Legislative Assemblies. As the heartland of the Gaddi ethnic group, the Bharmour area is classified as a ‘reserved’ constituency in which candidates must belong to a ST; it is also a tribal sub-district which provides increased budgets to promote education and affirmative action employment schemes.

Standing as the Congress Party’s candidate, Thakur Singh was first elected to the Himachal Pradesh Legislative Assembly in 1982 and has been returned as the representative for Bharmour on another five occasions since then – 1985, 1993, 2003 and 2012. Following the 2012 election he was promoted to serve as Forest Minister in the state government of Virbhadra Singh and also sat on the House Panel for the welfare of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. Gaddis throughout rural Chamba would tell me of how Thakur Singh – ever present and smiling paternally – was responsible for the building of roads, and the provision of water and electricity to their villages. Without Thakur Singh a relative couldn’t have secured the prized government job, and their children would have not had the benefit of a 10+2 education. Some said Thakur Singh used his power to reward his supporters with government contracts; his enemies whispered that his position as forest minister allowed him to amass wealth though the illegal selling of timber. Such activities were shrugged off as unsurprising – something all the big politicians did – or even positively celebrated as a sign of his reach and power. Thakur Singh Bharmour not only represents Gaddi people in HP’s State Legislature, he also demonstrates to Chamba’s Gaddis the possibilities of what might be achieved by a poor tribal boy from the remote rural backwater of this mountainous state.

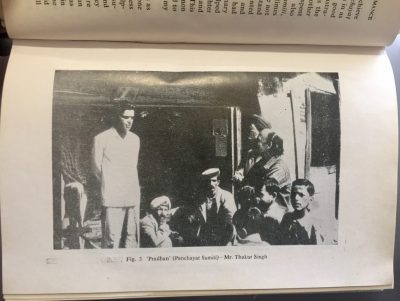

Over the years a series of encounters I have had with Thakur Singh have made me aware of the extent to which this politician has actively involved himself in defining the boundaries of what it means to be Gaddi. We first met by chance one spring evening at the Chaurasi temple which marks the sacred centre of Bharmour village. Discussing what it meant to be Gaddi he boasted of how he’d used arguments about common language, culture and religion to extend Scheduled Tribe Status to Gaddis living in neighbouring Kangra District. A later interview,[1] which took place at his home, covered the work he did to promote and protect the Gaddis’ ‘traditional occupation’ of migratory shepherding – an activity he claimed to have practiced himself in his youth. Representing ‘Gaddi-ness’ politically and culturally, it became apparent that Thakur Singh’s entry into the increasingly communal politics that has characterised India from the 1990s was informed by an anthropologist’s appreciation of identity. Veena Bhashin’s 1988 ethnographic monograph ‘Himalayan Ecology, Transhumance and Social Organisation: Gaddis of Himachal Pradesh’ contains a black-and-white photograph of a young man with oiled hair and a handsome face that held a trace of mischief. When Bhashin first arrived in Bharmour in 1976 it was the “‘Pradhan’ (Panchayat Samiti) – Mr. Thakur Singh” who had come forward to act as contact man, interpreter, guide and informant. In part, Thakur Singh owes his career to the success with which he combines the anthropological and the political – he is able to present social customs, behaviour patterns and village etiquette to outsiders and interpret for them what it means to be Gaddi. In return he brokers development schemes and affirmative action programmes for the benefit of his constituents.

To many Gaddis, Thakur Singh has been, for over thirty years, the living embodiment of their hopes and dreams for development. But there is also an awareness of the limits of what he can achieve. His relationship with H.P. Chief Minister Virbhadra Singh is illustrative of this. Thakur Singh – the loyal and guile-less tribal – is seen as Virbhadra Singh’s chamcha (lit. spoon; fig. side-kick) who sings and dances as a warm-up act on the campaign trail. While ‘Raja-ji’ is able to mobilise the broad coalitions of state level support needed to be Chief Minister, his Minister for Forests and Fisheries is constrained by coming from a remote and backward tribal constituency. Though Thakur Singh is keen to promote small-scale agriculture and romanticises the Gaddi’s shepherding traditions, it is little comfort to those among his constituents who feel trapped in these occupations and unable to move into the high-status, white-collar jobs, and government service jobs that are monopolised by the upper castes.

To many Gaddis, Thakur Singh has been, for over thirty years, the living embodiment of their hopes and dreams for development. But there is also an awareness of the limits of what he can achieve. His relationship with H.P. Chief Minister Virbhadra Singh is illustrative of this. Thakur Singh – the loyal and guile-less tribal – is seen as Virbhadra Singh’s chamcha (lit. spoon; fig. side-kick) who sings and dances as a warm-up act on the campaign trail. While ‘Raja-ji’ is able to mobilise the broad coalitions of state level support needed to be Chief Minister, his Minister for Forests and Fisheries is constrained by coming from a remote and backward tribal constituency. Though Thakur Singh is keen to promote small-scale agriculture and romanticises the Gaddi’s shepherding traditions, it is little comfort to those among his constituents who feel trapped in these occupations and unable to move into the high-status, white-collar jobs, and government service jobs that are monopolised by the upper castes.

The month before writing this, I followed the rough road through the mountains to Bharmour with the hope of finding Thakur Singh and interviewing him about recent political developments. Along the way I stopped off to see the newly opened Forest and Tribal Cultural Awareness Centre. Established by the Forest Department under the direction of Thakur Singh it contains a series of tableaus – one of a shepherding couple clad in traditional Gaddi clothes; another of the performance of nuala – a culturally defining religious ceremony in which a sheep is sacrificed to the god Shiva, whose abode Gaddis locate atop a mountain at the heart of the Bharmour constituency. Shiv-bhumi (the land beneath the holy mountain) is identified with Gaddern (the Gaddi heartland) the boundaries of which, in turn, correspond with the reserved constituency and tribal sub-district of Bharmour.

The month before writing this, I followed the rough road through the mountains to Bharmour with the hope of finding Thakur Singh and interviewing him about recent political developments. Along the way I stopped off to see the newly opened Forest and Tribal Cultural Awareness Centre. Established by the Forest Department under the direction of Thakur Singh it contains a series of tableaus – one of a shepherding couple clad in traditional Gaddi clothes; another of the performance of nuala – a culturally defining religious ceremony in which a sheep is sacrificed to the god Shiva, whose abode Gaddis locate atop a mountain at the heart of the Bharmour constituency. Shiv-bhumi (the land beneath the holy mountain) is identified with Gaddern (the Gaddi heartland) the boundaries of which, in turn, correspond with the reserved constituency and tribal sub-district of Bharmour.

Back on the road I passed a recently painted mural of Chief Minister Virbhadra Singh and MLA Thakur Singh that bore the words:

People have only this cry

Raja Virbhadra Singh for a seventh try

All of Bharmour is well-decorated

Thakur Singh all hail!

In November 2017 Himachal Pradesh went to the polls to elect a new Legislative Assembly. Though Virbhadra Singh – standing for a seventh time – managed to keep his seat, his party was overwhelmingly rejected by the voters. Thakur Singh Bharmouri was among the 15 Congress MLAs who lost out as the BJP swept to power.

Once I’d arrived in Bharmour I called at Thakur Singh’s house. It was locked up and there was no answer. The shopkeeper opposite said he had gone away to Pangi – a tribal area on the far side of the Pir Pangal range. What was he doing there? The shop-keeper didn’t know. But others pointed out that it might be the first stage of a campaign to win the ticket to be the Congress parliamentary candidate for the twin districts of Kangra and Chamba at the upcoming 2019 National election.

Once I’d arrived in Bharmour I called at Thakur Singh’s house. It was locked up and there was no answer. The shopkeeper opposite said he had gone away to Pangi – a tribal area on the far side of the Pir Pangal range. What was he doing there? The shop-keeper didn’t know. But others pointed out that it might be the first stage of a campaign to win the ticket to be the Congress parliamentary candidate for the twin districts of Kangra and Chamba at the upcoming 2019 National election.

Footnotes

[1] I went to his house and found him wrapped up in bed wearing pyjamas, a cardigan and a woolly hat owning to having a bad cold.

Dr Richard Axelby is a Research Associate in the Department of Anthropology & Sociology at SOAS University of London and Programme Manager for the Global Research Network on Parliaments and People. His research interests span three interlinked areas: poverty and inequality; identity, history and citizenship; and agrarian change, natural resource management and the environment.