Dr Zoë Marriage argues that Jair Bolsonaro’s victory in Brazil’s recent elections hinges on a political rhetoric that legitimises anger and violence. This is symbolised in the fatal stabbing of a leading capoeirista on the first night of the election, an event which brought together the diverse global capoeira community, whose origins are firmly rooted in the discourse of struggle and resistance against precisely the nationalist and fascist propaganda of Brazil’s new President.

On 28 October 2018, 55% of Brazil’s population voted for a far-right president who has used aggression against groups – women, blacks, indigenous people, and the LGBT community – to further his political ambitions. There are two questions that arise with regard to the outcome of this election: why do people vote for fascism and why have the developmental gains of the last couple of decades not resulted in a more inclusive security agenda?

The election has stirred Brazil; each side staged massive rallies while fake news played a now-familiar part in disorientating political engagement. Families have been rent apart as Jair Bolsonaro’s populism swept the country and ex-president Lula was kept in jail. The problems presented to the public during the election as needing resolution included the downturn of Brazil’s economy; violent crime and gangs; and distrust of traditional political parties, particularly the Workers’ Party (Partido dos Traballhadores, PT). And it is these issues that contributed to Bolsonaro’s election. Refusing to take part in debates, Bolsonaro’s campaign was characterised by angry shouting, and improvisation with anything at hand (or sometimes just a hand) to pretend that he was holding a gun.

Bolsonaro’s rise in popularity has elements in common with the Brexit vote or Trump’s presidential victory: the unthinkable became possible, and the possible became inevitable. It played out in slow motion as the first round of elections returned Bolsonaro with a practically unassailable 46% of the vote. The northeast was the only region that did not support him in the first round. This lack of support is not surprising given Bolsonaro’s hostility towards north-easterners and the fact that many of them experienced direct benefits under Lula’s presidency. But the rejection of Bolsonaro in the northeast throws into starker relief why those with higher levels of education, service provision and wealth would be strung along by the jingoism.

On 8th October, the night of the first round of elections, Mestre Moa do Kantendê, a master of the Afro-Brazilian martial art of capoeira, was killed in a bar in the suburbs of Salvador, the capital of the northeastern state of Bahia. Following a political altercation, his attacker fetched a knife and stabbed him in the back. By dawn, social media had relayed across the world the passing of a black man, a capoeirista and almanac of Afro-Brazilian music and culture.

Mestre Moa’s death demonstrates how the questions – of why people vote for fascism and why developmental gains have not produced a more inclusive security agenda – are intertwined. Mestre Moa’s assailant, a black man from the same neighbourhood, gave a telling account of the night, claiming that Mestre Moa had called him a homosexual. The excuse for his violence channelled Bolsonaro’s politics. Forms of development and security that lift millions out of poverty in a few years require sustained negotiation, and commitment to progressive politics. Bolsonaro offers a simpler security solution: violent exclusion. People vote for fascism because it strips out the politics and ethics of security and development, and gives them licence to satisfy anger. And it can be attractively packaged up for those who want to believe in it: the spectacle of scores of dancers jumping around for Bolsonaro has been a choreography of joy, intimating normality and equality through the line-dancing and casual uniform of jeans and yellow t-shirts.

Bolsonaro’s problem-solving rhetoric and pretend-gun-waving frames his realist perspective. Critical security studies challenges the assumptions of realist thinking thus: the focus on war and violence, it argues, has never captured the most severe threats to human populations; realism did not explain the demise of the Soviet Union; and weapons are not dependable tools or routes for providing security. As critical security studies gained pace in the early 1990s, one conclusion was ironic: realism is not reliable at capturing, explaining or justifying reality. Its narrative is a fantasy – like a pretend gun; it impresses only those who enter into its imaginary. It is a double irony, because in making this critique it is the non-realists who present a perspective from which, in reality, it is possible to analyse and resist.

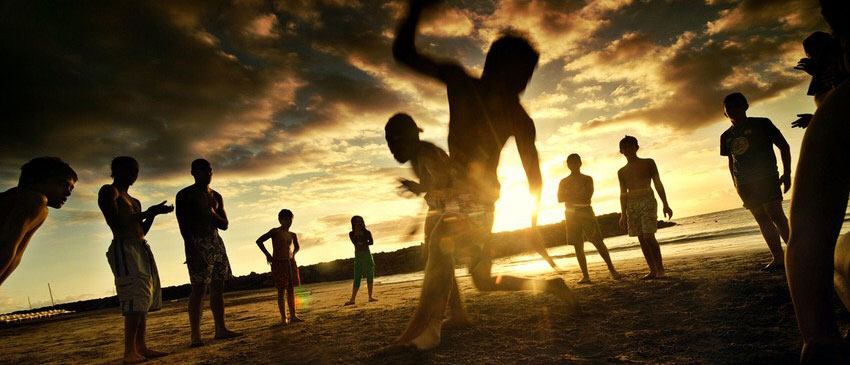

In the streets of Pelourinho, the iconic centre of Salvador, an area used in the time of slavery as a whipping post, capoeiristas gathered to mark the death of Mestre Moa and denounce the political tide of the country. The commemoration brought together capoeiristas from diverse styles of an art that is not characterised by ecumenism. It was led by the five-foot music arc, the berimbau, which simultaneously represents and communicates a history of oppression and struggle; and photos and video footage were shared via the internet with a global community of players.

Capoeira frames a discourse of struggle that problematises inequality, mobilises in structural violence and maintains the possibility of other outcomes. For more than a hundred years, the narrative of capoeira has resisted successive iterations of nationalistic propaganda by communicating the value of its black and working-class heritage through song, movement and ritual. It is critical in exposing the exclusion and violence of Brazilian history and its legacies. Unlike critical security studies, though, the discourse of capoeira remains independent. In the fluid trading of kicks and acrobatics that make up the art, it is the dodge – the esquiva – that keeps the game in play, celebrates in adversity, and creates the conditions to escape the inevitability of violence.

Zoë Marriage is Reader in Development Studies at SOAS, University of London, where she also convenes the Violence, Peace and Development research cluster. Dr Marriage’s book, ‘Cultural Resistance from Below; power and escape through capoeira’ will be published by Routledge in 2019.